IMAGE DESCRIPTION: An ink drawing of a house houses a far-more-realistic image of a brain seen from above. The house has feathery and perhaps angelic wings. A single crow flies far above the house.

ISSUE 42

CONTENTS

SEPTEMBER 2018

Miguel Angel Soto

Douglas Cole

Freda Epum

Heather Kirn-Lanier

Elliott Freeman

ART: Christine Stoddard

Akira Devine Mattingly

Jennifer Stewart Miller

Lysbeth Em Benkert

Holly Day

Sonia Greenfield

CONTRIBUTORS

Miguel Angel Soto

MIDWESTERNER

I am a dreaming Midwesterner,

living between sky and sea.

Despite the distance, the sea arouses

the sky with her wave-breaks,

rubbing the backs of heavy rock. Both

women in their saturating blues,

waiting for the other to reach out

of her depth to collide.

On the sandy shores, I watch the clasping

of hands, belonging to two

masculine, sculpted bodies, closing

in on one another’s starfish lips—

tantalizing.

I am a rigid reef—elbows and shoulders decorate

the sandy shores, letting the granular

pulsate into my spongy pores, a laying

sessile, forgetting the imperfect

alignment of my spine to

my hips.

I am waiting for the outpour to

take me in and drown me—

ripples are enough to wash me over,

coursing between my toes

coursing between the soft anemone hairs

on my legs, breaking off into streams,

surging up into the seams of my shorts,

caressing the softest parts of

my flesh.

When I wake, all that’s left is

seafoam drying in the humid

heat dripping off my mantle-head—

a reminder of the long reach.

Douglas Cole

FAST AWAKE

I am reaching for the amethyst

center of the sea

trying to name every tree

on the peninsula

but in the back of my mind

I’m still worried about money

and calculating if I don’t eat

I can save enough for school

how many pounds must I shed

to clear the cobwebs of hunger

while the dog scratches at the door

with that deep-woods look

room consumed by drinking rounds

crows collecting as time shifts

and I am back in this brackish

current between a falling apple

and a puff of smoke

so I ripple my way

and sometimes come up for air

sometimes eat the earth

with eyes like meteors

burning in a green bay

Freda Epum

THE AFRICAN DREAM

I’m watching TV with my dad, HGTV is on. It’s probably House Hunters or Flip This House.

We sit together on a tattered sepia colored leather couch in a four bedroom with 2.5 bath, eagerly

waiting for the reveal of the much larger home with granite countertops and crown molding.

Casually, my dad tells me of the hut that he used to live in while a commercial flashing an

advertisement for Tiny Houses appears on screen. How distant I feel from the life I would have

had but never will know. A life with electricity that comes and goes, a life my mother had

fetching water for her grandmother to take a shower, a life of cars that don’t obey the rules of

four-way stops, a life of pink doily dresses and braids too tight—done every six weeks or so.

We moved around the time I was eight years old, maybe seven. Dust in the desert air smelled

like the early 2000s, chubby cheeks, skateboards, yellow school busses, and otter pops. Wood

hoisted off the ground on stilts, became walls, became bedrooms, became memories, became

nightmares. I take pictures with my siblings in front of the structure that will become another

salmon colored adobe house in a sea of salmon colored adobe houses behind gates outside the

city.

I look out the hexagon window and see the ghost of my mother, sitting in her dorm room in high

school surrounded by what must be trendy clothing, posters, hair products and lotion. She sits

with no smile, unusual then but a habitual pose now. I’m wearing a frilly lace shirt with Ankara

fabric and I try to taste the Jollof and shea butter and sweat in air that my dad tells me engulfs

you as you step off the plane and find yourself in Nigeria.

In the evenings, I picture every detail of my future life there. This period of imaginary

Africanization fixes me. Rebuilds me from broken, remolds my tongue, deconstructs the

Atlantic. I zigzag against the current of the borderlands, never arriving.

I wrap my hair in golden, sipping on Heineken hoping the splash as it touches my gums will

change my cadence from meek to boisterous. Hoping it will transform me into someone that

actually like Heineken.

As a little girl, I steal my dad’s whicker-like hat pretending to be on a safari because the

American school system tells me all about the country of Africa. They shrink down my continent

until I can fit it into my pocket, muddying my white flower dress with its rich pigment. I color

the walls brown with Crayola to create mirrors of other selves. Shades of brown like church

doors and my father’s suits. He sits me down every Easter from five to twenty, telling me fables

of Jesus. I scratch my face to check for stubble and grab the glasses from his nose, adjusting my

collar as if I’m wearing a tie. I play in makeup and don gold hoops, wondering when these

costumes will become markers of my new identity.

If I were to be a model daughter of an Igbo family, I would be holding a baby—six pounds,

twelve ounces—their head tilted as I cradle small skull and tush, milk that too remolds the

tongue. The air smells of African sweat and mashed yams. I am 24 years old with my first-born child

just like my mother. And I wonder what happens to the souls of mothers who have sacrificed

themselves for the sake of their children’s success. I wonder what happens to her soul when she

arrives in America, too foreign for here. I wonder what happens to her soul as goodbye is uttered

to her country. I wonder whether she cried the entire flight.

Heather Kirn-Lanier

BEFORE WRITING BACK TO A FRIEND WHOSE MOTHER IS DYING, YOU STARE...

at the empty fireplace.

Don’t make it a metaphor.

That the soot in the fireplace has smothered

every brick but where the fire burned,

that the bricks now hold a ghost

of flames that once flickered there

doesn’t mean anything.

Just write your friend back.

You have to figure out how to fill

an email with nothing

but a bed of silence, and the silence

can’t be empty,

though it must be empty of your own grief.

Your grief is an ornery dog

that wants to play. Tell it to sit.

Then it will offer the obvious from its teeth like a bone:

Metaphors of sunsets will make you both barf.

Everything happens for a reason

is the greeting card from an unlikable god.

This too shall pass is precisely the problem,

the word pass like a swoosh, so fast it’s gone.

Tell her you will lie down next to her. Tell her

whatever mad pulse her heart drums out,

you will let yours do the same.

Do not dare tell her the truth:

That it will be like screaming into a black hole,

the wanting

so bad her body will think it’s grown

a thousand arms, grabbing what’s gone.

That organs she doesn’t have

will throb inside her.

That she might fall into the black hole

and that no one,

not even you, can join her.

Elliott Freeman

FULL-TILT HYPOMANIA BRAIN BEAUTY

Everything is a lugnut bell-song fit, and when it’s right, it’s impossibly right; my life is a Rube

Goldberg: here, the Zippo cuts a thread with spear-prick fire; here, a croquet ball gutters into my

toaster; my blood is full of acoustic rock, my feet navigate sidewalk cracks to hopscotch rumbas–

serotonin thrill, trill of birdsong and catcalls, there are no full stops–life rides a run-on em dash

like I’m surfing on a bronco’s back; trick of smile, thrumming guitar neurons hooked to a tilted

amp; everything soundtracked by the Beach Boys and I love things that I always should have

loved: the way a good joke purples a friend, the breathless moment before the laugh takes hold

and the way jaw muscles draw back like tightened crochet loops.

It does not last forever. It does not last long. There’s a voice that says, too often correctly: This

Red Bull Buddha socialite is only a beautiful symptom.

Christine Stoddard

GIRL WITH CAMERA

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: In this photograph, a woman sits on a gray cement floor, in a corner between gray cement walls. Her head is bowed, and she holds a camera in both hands and behind her back. She is poised to take a picture. She has wavy brown hair. She wears a red velvet gown and a black exercise bra or tank top.

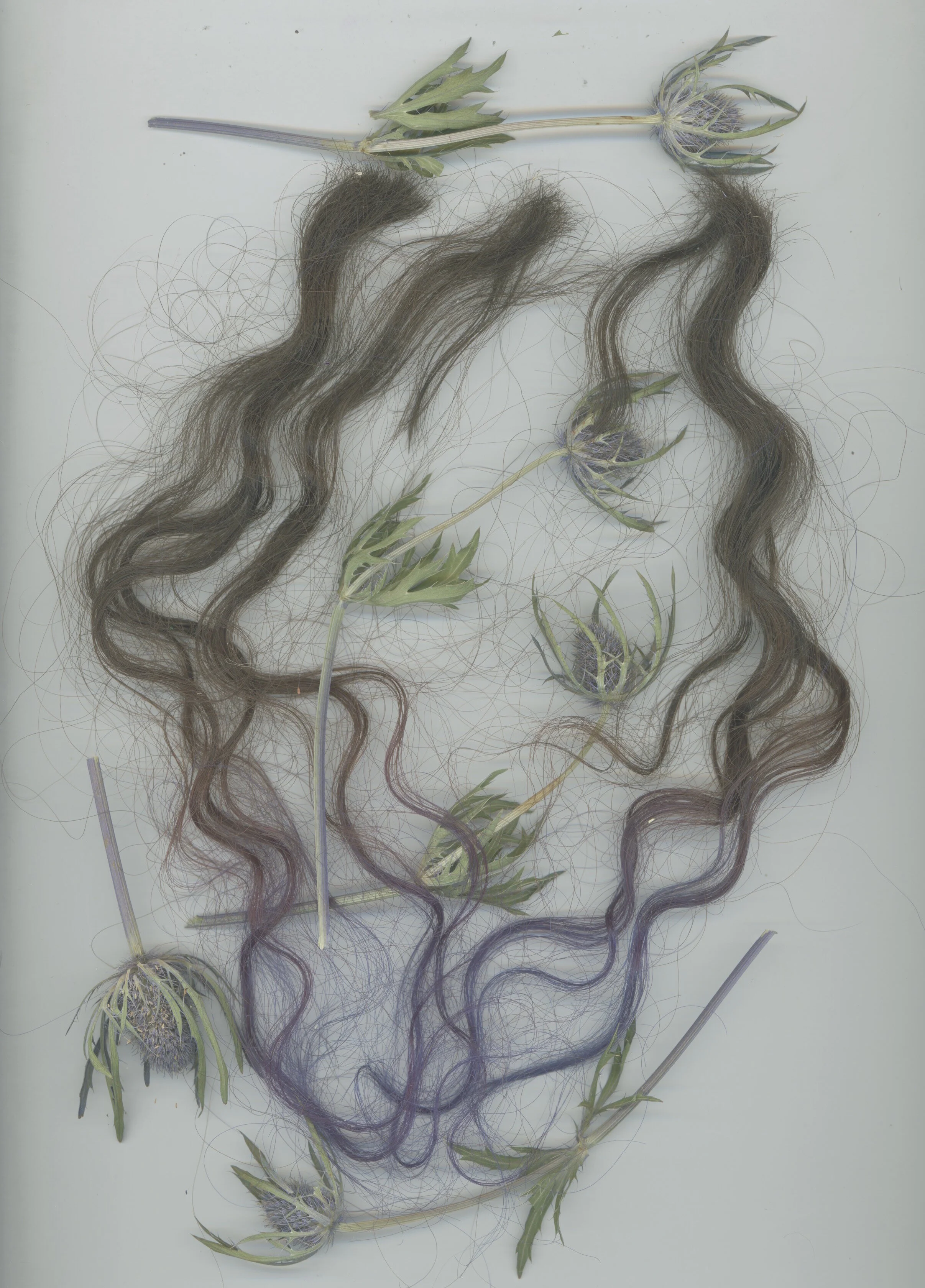

SCOTTISH THISTLES AND HAIR

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: In this mixed-materials collage, the hair is pale brown and wavy and appears in three horizontal strands that define the image. The Scottish thistles are purple and green. Both rest on a pale blue background.

MIRROR MASK

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A person in a black dress, boots, and a mirrored mask stands in front of a garage door. Their hands are up to narrow their field of vision or catch something. The garage door is brown and set in an industrial doorway. It has white, scrawled graffiti and a "private property, no trespassing" sign. The foreground of the photograph is obscured by reflections as if the photograph was taken through the mirrored mask.

HITTING THAT CRAVING

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: Two anatomical dolls (one male and one female) lie across brown clay shaped to resemble a piece of meat or female genitals. The male doll appears to be hitting the clay with his fists. The female doll lies crumpled beside it with both legs bent backwards. The clay rests on a pile of tan dust.

PUNK FLASH

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A hank of hair (long, brown at one end and dyed purple at the other) is bound to a camera with string or twine. The camera is dark metal, and the lens is covered. The whole object floats in front of a white photographic backdrop and the black background behind it.

PERFECT LIKE YOU

Video by Christine Stoddard with music by Black Pudding Poetry. © Quail Bell Press & Productions.

Artist statement:

I have been aware of my body for as long as I can remember. For a long time, shame was attached to that awareness. Unfortunately, too many women and gender non-conforming people can identify with that feeling. Puberty did not make things easier. Sex only complicated it. I have always been interested in body politics, but right now I'm using my artwork to investigate bodies and the Internet. The Digital Age has both increased our displacement with bodies and also made it easier than ever before to find and celebrate body positivity.

Akira Devine Mattingly

DIET

It is not a form of self-harm.

It is a practice in self creation.

See the body as a catalyst,

as only a means to an end,

in the pursuit of perfection.

Small bites. Thoroughly chew.

Memorize perfect portioning.

Track meals. Limit calories.

Shrink your stomach.

Drink coffee. Smoke a cigarette.

Steal your mother’s laxatives.

Dread the fullness,

the way food settles heavy

inside like sunken bones

in the river Styx.

Skip meals until it is natural.

Train your body

to desire only what you give.

Forget the gnaw of hunger

as it eats away at flesh.

Dry heave into the toilet.

Congratulate yourself

for having nothing

to give, nothing to lose.

Admire the roadkill

with their glassy eyes

and flattened insides.

Jennifer Stewart Miller

CLEANING THE NIGHT BASEMENT

On a ledge in the back

room I can

dimly make out

a nest made of decaying

fur and grey sticks—big like

a squirrel’s nest I don’t

want to see any

of this but a rat

fat like an opossum

uncurls and

casually leaps down

brushes past

my stiff legs and

morphs into a

raccoon, which squats

and stares through its mask—

something

gnaws at me and I squeeze

through a little hole

my mother’s boyfriend

and I

lie on

a twin bed in her room

watching the only TV—

He slides his big

hand

down

under the waistband

of my pajamas

his fingers

insinuate their way

under the elastic

of my

underpants

and

stroke my newish

little mammal patch.

He

pauses

bites back

most of

a moan

withdraws his

hand—

but not

the rat

and not

its doppleganger

the raccoon

with its sorry

little hands.

Lysbeth Em Benkert

FORENSIC EXPLORATIONS

where did that come from?

it’s my morning mantra.

Climbing out of the shower

smoothing lotion over my skin, I

wince.

My fingers brush an ache that

wasn’t there yesterday—

a new bruise on my thigh,

a tender spot on my shin,

fuzzy photonegatives

of clumsy navigations

a sharp corner,

the long line of a desktop,

a purple splotch—

indeterminate

shadows that inscribe

accidents on a mortifying

palette.

Mornings are my reckoning.

in the bright lights of

my solitary strip search,

my fingers slide over

my limbs, confront my

irrefutable existence,

the fact that my

body

takes

up

space,

that it bumps into

things,

that it doesn’t always fit,

that I curse it

and clothe the evidence

with plausible deniability,

disavowing substance,

perjuring myself

in pursuit of grace.

Holly Day

AT THE WHEEL

The clay warps and grows smooth beneath my hands, opens into

A mouth I can pour my day into. Inside this pot between my hands

Is a prison for the fights I walked away from, the answers I should have shouted

The anger that’s been balled up in my stomach, like another lump of clay

All day long.

I press the side of the spinning pot and now it’s a vase for flowers.

I imagine the flowers that will go into this vase filled with hate

Wonder if they’ll still bloom for days after being cut, ignorant of the poison

I poured into this vessel, or if they’ll wither and die immediately after being set in water

As if touched by a ghost, or a curse, or disease.

Sonia Greenfield

I WAS WAITING FOR MY SHIP TO COME IN

on shore, a harbor, at the end of a wooden pier

jutting out to accommodate a deep keel, tides

rising and falling, following my own cycles. In this

stasis, I counted each new gray hair, counted every white

cap in the distance, counted pelicans in their heavy

formations of aircraft, counted all the leapt fish.

Against the horizon, a vessel’s blocky silhouette

appeared, and because I had been patient for this long,

I knew I could keep up with waiting, but because

I was tired, I sat cross-legged where the boardwalk

dropped off to the green below. When the moon’s

hook of bone was hoisted, I laid down facing the water

with unknowable night in front of me, tangy breezes,

and a shape steaming through the darkness. In the ache

of morning, I got to my feet as the sun came up

from hills behind me and tipped its light

into the valley’s cup only to find before me a mistake

of perspective. That which should have been a ship

was just a Boston Whaler. I don’t know why the magnet

of myself that drew it to shore didn’t know that proximity

wouldn’t make it grow. Still, I could captain this,

I thought, so I tied off the bow line to a rusty cleat,

and clambered into a boat made for no more than three.

I wouldn’t call it seaworthy. It can’t weather squalls

or swells— it's pretty small— but it hugs a shoreline

just fine. I can give it gas, trace a v's wake around

the land’s shape, and call it all mine.

Issue 42 Contributors

Lysbeth Em Benkert's first chapbook, #girl stuff, is forthcoming later this year with Dancing Girl Press.

Douglas Cole has published four collections of poetry and a novella. His work has appeared in anthologies and in The Chicago Quarterly Review, The Galway Review, Chiron, The Pinyon Review, Confrontation, Two Thirds North, Red Rock Review, andSlipstream. He has been nominated twice for a Pushcart and Best of the Net, and has received the Leslie Hunt Memorial Prize in Poetry and the Best of Poetry Award fromClapboard House. His website is douglastcole.com.

Holly Day's poetry has recently appeared in The Cape Rock, New Ohio Review, and Gargoyle. Her nonfiction publications include Music Theory for Dummies, Music Composition for Dummies, Guitar All-in-One for Dummies, Piano and Keyboard All-in-One for Dummies, Walking Twin Cities, Nordeast Minneapolis: A History, and Stillwater, Minnesota: A History. Her newest poetry collections, A Perfect Day for Semaphore (Finishing Line Press), I'm in a Place Where Reason Went Missing (Main Street Rag Publishing Co.), andWhere We Went Wrong (Clare Songbirds Publishing) will be out mid-2018, with The Yellow Dot of a Daisy already out on Alien Buddha Press.

Freda Epum is a Nigerian-American writer and artist from Tucson, AZ. She makes work about black bodies, displacement, dis/abilities, and longing. Her work has been published or is forthcoming from Bending Genres, Cosmonauts Avenue, and Rogue Agent. She is a Voices of Our Nation/VONA fellow and is currently working on crafting experimental vignettes of prose and poetry for a memoir about depression. She is a creative writing MFA candidate at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio.

Elliott Freeman is a poet, writer, and educator in the mountain hinterlands of Virginia. His work has previously appeared in Issue 16 of Rogue Agent, in addition to Rust+Moth, Blue Monday Review, and Liminality. If you want to stalk him, he makes it pretty easy at www.emfreeman.com.

Sonia Greenfield was born and raised in Peekskill, New York, and her book, Boy with a Halo at the Farmer's Market, won the 2014 Codhill Poetry Prize. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in a variety of places, including in the 2018 and 2010 Best American Poetry, Los Angeles Review, Massachusetts Review, and Willow Springs. Her chapbook, American Parable, won the 2017 Autumn House Press/Coal Hill Review prize and was released this past April. She lives with her husband and son in Hollywood where she edits the Rise Up Review and directs the Southern California Poetry Festival.

Heather KIrn-Lanier is the author of two award-winning poetry chapbooks along with the nonfiction book, Teaching in the Terrordome (U of Missouri, 2012). Recent poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Image, Rhino, and Barrow Street. She teaches at Southern Vermont College and her second nonfiction book, a memoir about raising a daughter with a rare chromosomal syndrome, is forthcoming from Penguin Press.

Akira Devine Mattingly is an emerging writer and an undergraduate student at the University of Louisville pursuing a BA in English with minors in Creative Writing and Philosophy. She lives in Louisville, KY with her two cats.

MIguel Angel Soto is a queer, brown boy, who writes for the exploration of political identities, and intellectual and emotional intelligence. He’s an editor for Jet Fuel Review, a literary journal based out of Lewis University in Romeoville, IL. He also blogs under the guise xicanxlibre1596.wordpress.com.

Jennifer Stewart Miller holds an MFA from Bennington College and a JD from Columbia University. Her poetry has appeared in Green Mountains Review, Harpur Palate, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Jabberwock Review, Raleigh Review, and other journals. She’s a Pushcart nominee, the author of A Fox Appears: a biography of a boy in haiku (self-published 2015), and lives in New York.

Christine Stoddard is a Salvadoran-American artist, CUNY grad student, and the founder of Quail Bell Magazine. Her work has appeared in the New York Transit Museum, FiveMyles Gallery, the Ground Zero Hurricane Katrina Museum, the Poe Museum, the Queens Museum, and beyond. Last summer, Christine was the artist-in-residence at Annmarie Sculpture Garden, a Smithsonian affiliate in Maryland. Her latest book, Water for the Cactus Woman, is now out from Spuyten Duyvil Publishing (New York City).