Teow Lim Goh talks about embodiment

and writing Faraway Places

The epigraphs to this book are so powerful. When I read them, they truly influenced my interpreting Faraway Places as a collection not just about places, but one that explores the intertwined nature of bodies, especially the female body, with the bodies of flora, fauna, earth, and water. What motivated you to write such a collection?

I’m glad you saw the conversations between the epigraphs and the poems.

I think of Faraway Places as an accidental book, in the sense that many of these poems started as “found” text from my drawer of discarded drafts. Several years ago, after I turned in the final manuscript for my first book, I struggled to figure out what I wanted to do next. Looking back now, I see that I was also burned out and I needed to refill the creative well.

In this limbo, I went back to old drafts of essays and poems. I saw that while there were good reasons why I had put them aside, there was also a primal energy in the writing. I captured the lines and images that stood out and started working them into new poems.

I felt I was onto something, but I didn’t know what it was. I worked by instinct. I found that if I thought too much about what I was trying to do, the poems would not come. At some point, I felt I had exhausted this vein of writing and decided to see if I could put them together as a book.

I printed out the poems and started shuffling them around on the floor. It took a few weeks, but I saw there was an implicit story that I was trying to tell. Many of the discarded drafts that became the source texts of this book were from my travels in the American West in my twenties, trying to figure out who I was and what kind of writer and person I wanted to be.

The essays I had published from these travels wove history, nature, and experience to discuss larger subjects such as immigration and art. And in these travels, I developed the poetry project that has kept me busy for much of the last decade, which is to recover the histories of Chinese immigrants in the Old West.

When I finally put Faraway Places together, I saw I had been writing a shadow text. I saw that in my travels, I was not just contending with the “big” questions of history and identity, but I was also learning how to inhabit my body after trauma and dissociation. Many of the source texts were nature descriptions that editors had cut. They were excessive for the original essays, but I see now it was in trying to name and describe the natural world around me that I taught myself to trust what I could plainly see and experience.

In “January,” it says “bearing witness is the deepest form of love” (34). This collection bears witness to all kinds of places, from rainforest to mountains to desert to ocean. Did the traveling to witness such places come before the poems, or did you already have some of the poems, which motivated you to travel and write the rest of the collection?

“January” was one of the last poems I wrote for this collection, though I did not know it then. I had been thinking about the line “bearing witness is the deepest form of love,” which I found in an old draft, when I went for a walk around the lake near my home. It was in January, of course, and on a sunny day after a deep freeze. And it was an urban park, with a major road next to it, but given that this is Denver, there were also gorgeous views of the Rockies.

I did not set out thinking that I would write a poem. But I started composing lines in my head and typed them into my phone. And I saw that while this place was not the wild nature that we often exalt, I was bearing witness to the stasis and change that was winter. I was bearing witness to how our lives were all connected. I still had to work on making the phrases I had recorded into a poem, but the seeds of it came unexpectedly on that walk.

I find witness to be more of a mode of being and thought than action. We can teach ourselves to pay attention and find the precise language to testify to what we can see for ourselves. It is a practice that we internalize and bring to bear in our everyday lives. And in observing nature, I also learned to bear witness to injustice, whether in private interpersonal dynamics or on a sociopolitical level like in my work on the Chinese in the Old West.

All of that to say, there was a push and pull between travel, memory, and writing. I rarely travel with the intent to bear witness, but when I’m thinking about something, like a line from one of my old drafts, it colors much of how I perceive the world as I go about my life.

JANUARY

Geese gather on the lake, on the border

of water and ice. I walk on the shore,

watch the birds waddle and lift their wings

as if they wanted to fly. They swim

in a blue like the blue of the sky, feeding

on grasses, maybe a minnow. The sun

casts its last rays on the mountains beyond

the city, where the snow is on the verge

of breaking – and I keep thinking, bearing

witness is the deepest form of love.

In “Archives,” the speaker says, “I cannot seem to document/my own life./..../Yet things/come back to me/in flashes. Sometimes/I write them into fictions” (13). In “Autobiography,” the speaker says, “We invent: this is who I am” (30). In what way does inhabiting these places, witnessing them, also work toward an invention of the self?

I grew up with a sense of self that was defined by others, to the extent that as a child, I could not write the word ‘I’, for behind it was only the terror of the void. I internalized the stories that family and culture imposed on me—that I was not strong, not competent, not credible, that I should make myself small to be acceptable. Suffice it to say, it did not bring me to a good place. And when I became an adult, I knew on some level that I had to build a real foundation for my life.

The threads all blur now, but my travel, witness, and writing fed each other in ways that helped me build a sense of self. Writing is at the core of it, ultimately, for it is through writing I learned to narrate the world, be it my internal life or the history of a place I visited. It is through writing that I could build a richer and stronger story for myself.

At the same time, a large part of the mythos of the American West is that it is a place to escape the past and reinvent the self. It is a fantasy, of course, but it has been wielded to oppress non-white peoples in the West—the indigenous peoples, the Hispanic communities who did not cross the border, but the border crossed them, and yes, the Chinese migrant workers who I write about. But we can rewrite this myth too.

Click to purchase Faraway Places

from Diode Editions.

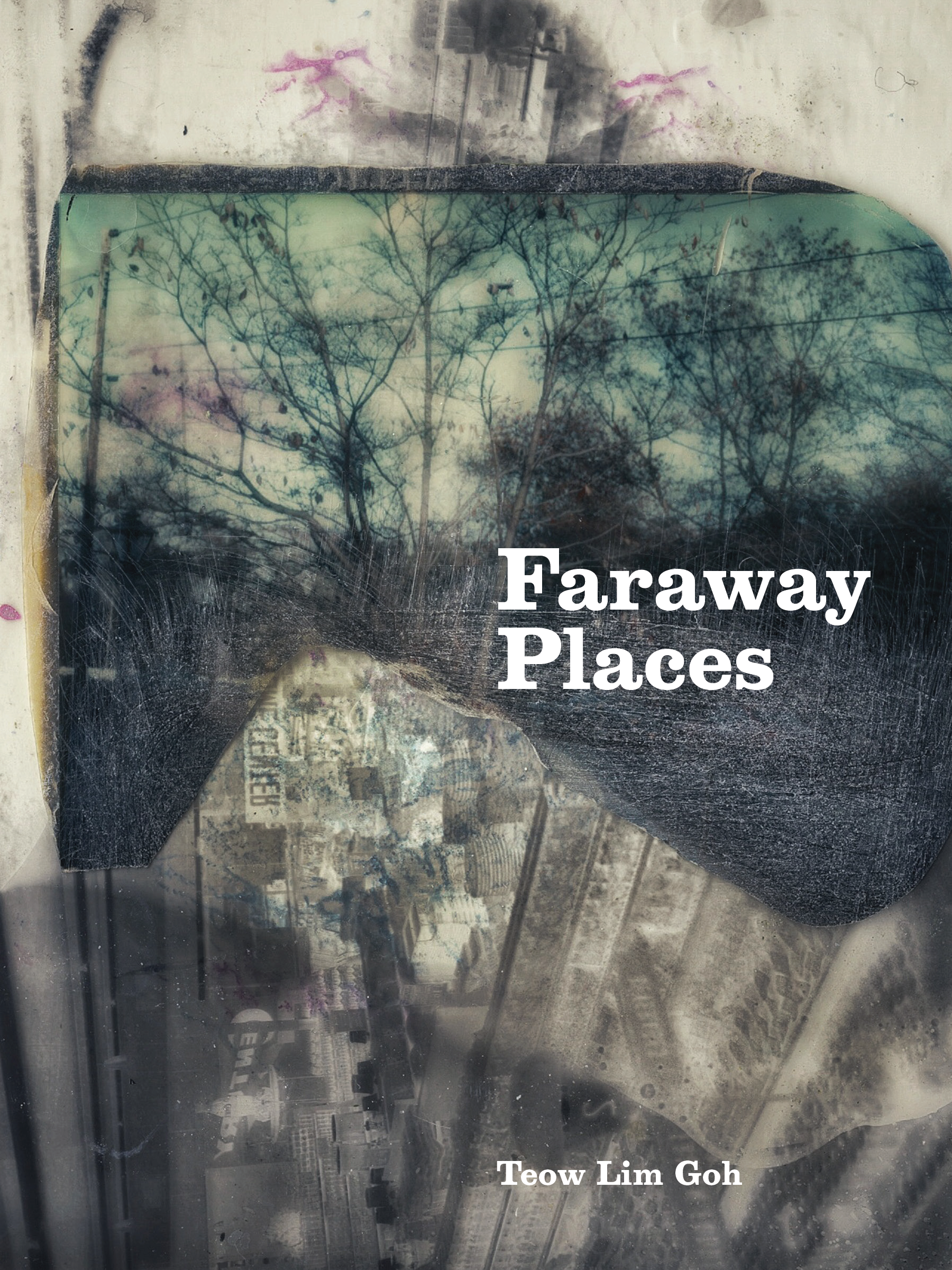

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: This book cover features overlapping images of a city seen from above (at the bottom of the cover) and the trees, brush, and telephone poles beside a road (in the middle section of the cover). The trees and brush seem to be seen through green-tinted glass while the city and the top of the cover are black and white. The title appears in white type near the middle of the cover. The author's name appears in white type at the bottom.

Please share with our readers a list of 5-10 books and/or artists you think we should read right now.

Melissa Febos’ Girlhood. I am still working through it, but she has created new frameworks to contend with the dark parts of girlhood. Much of it feels unspeakable precisely because we don’t have the language to talk about it, and Febos shows us some ways we can break this silence.

A lot of what I write looks out into the world rather than within. But I have a special affection for women writers who create lyrical, elliptical, and interior works. Some books I read as I worked on Faraway Places include Clarice Lispector’s Agua Viva, Louise Mathias’ The Traps, Cynthia Cruz’s Wunderkammer, and Lo Kwa Mei-en’s Yearling.

Some Rogue Agent fans are just beginning to explore what making poetry about the body would look like for them. What advice would you give to someone looking for new ways to imagine embodiment, beyond the literally described experience of the body?

Writing the body is a lot more than writing sex and desire, though it certainly encompasses both. A decade ago, I took Lidia Yuknavitch’s “Ecstatic States” class, and her first assignment was to describe a sexual experience between ourselves and anything but another person. The idea was to expand our ideas of eros and embodiment, merging and connection. One of these poems grew directly from this assignment—I’ll let you guess which.

I don’t remember who said that the body remembers what the mind would rather forget. But I find that writing the body is a lot about learning to heed our instincts, going deeper when it gets uncomfortable, quieting the critic’s voice in our heads, and finding the authority that each of us have in ourselves. When we are embodied, we trust ourselves to tell the truth, whether about our lives or the larger forces of history. That is the real power of this work.

Teow Lim Goh is the author of two poetry collections, Islanders (Conundrum Press, 2016) and Faraway Places (Diode Editions, 2021). Her essays, poetry, and criticism have been featured in Tin House, Catapult, Los Angeles Review of Books, PBS NewsHour, and The New Yorker.

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: Teow Lim Goh poses for a formal picture against a gray background. She has short dark hair, dark eyes, and a small smile. She wears a white gauze overshirt and scarf over a black shirt.

.