IMAGE DESCRIPTION: The image shows a tuba with butterflies emerging from the horn. Two wind gusts, amoebas, or clusters of bubbles are either tied to the tuba's mouthpiece or flowing into the tuba to emerge as butterflies.

ISSUE 26

CONTENTS

MAY 2017

Amy Miller

Jessica L. Walsh

Ana C. H. Silva

INTERVIEW: ire'ne lara silva

Jacklyn Janeksela

Jessica Abughattas

Leah Welborn

Cheyenne Nimes

ART: Stephen Langlois

Leslie Contreras Schwartz

Shevaun Brannigan

Kim Sousa

CONTRIBUTORS

Amy Miller

LOOSE RIB

It wants to invent

somebody. At night,

it stands on end,

staring out the window

at the bone-faced moon.

If it could, it would

unscrew its anchor

and embrace a boomerang,

flash half hula-hoop,

half bracelet into the blackened

sky. But soaked

in a brine of blood,

it floats in the body’s

museum, tapping

the lung with a long,

impatient finger.

Jessica L. Walsh

FROM HIS HEART A SPEAR

Antlers grew from his temples

human skin ceding seamless

to bone and velvet.

That first morning, as I leaned closer to look,

he held my face in his hands

and soon my head ached

with longing and phantom pain

as I wondered why I had none.

In spring his neck darkened

and a hard bump pushed outward.

By month’s end a single black feather

lay flush against his skin

as natural as a raven’s.

Sometimes his hands were bark,

and other days, cool scales.

Whatever he became, I stayed myself,

growing content to fatten and dim

in favor of his marvels.

Woman on the Right

Having once been sliced open

—for mirror-twins, it turned out—

oneness, wholeness

are suspect

I believed in the soul right away

when I saw them

remarkably similar bodies

perfectly distinct energies

one of earth and fire

the other of air and water

and what is my other double?

I might be a bird

Don't be fooled by the smart black shoes that pinch my feet

or my conventional skirts

The space above my neck and shoulders

is just sky

Woman on the Left

Having once been split open

sliced open with a bold knife

black thread passed through holes

of my flesh

made by a blood slicked needle

not completely healed

open to the world

open to love

a feeling of being un shut

seamed but un whole

my scar tugs at itself when I stretch

my belly

I know there is danger

who knows what will come out

slime a broom parts of insects broken buttons

feathers dust

nothing — any more — as luscious

as my children

steel circles my calves

when I pause mid step to think

maybe I am made of

just filaments shadows interstices

not flesh bone blood and something called me

ire'ne lara silva talks about embodied poetry

and writing Blood Sugar Canto

Please describe your journey toward writing poetry that reflects on the experience of living in the body. Have you always written this way, or did you come to it over time?

Time. People have the idea that to write from the body is somehow more instinctual, more emotional, and less intellectually or aesthetically rigorous. I think the opposite is true. It takes ongoing work and thought to peel away layers of artifice. To peel away the habit of untruths and the way we hide when language and image are formulaic constructions. It takes discipline to listen to the body and learn its language. There is nothing easy about revealing your fears and hesitations, your pain and history.

I said something last year about Gloria Anzaldúa’s work (specifically, Borderlands) that only seems truer the more I reflect on it—that the work of certain writers has a powerful effect/affect on us because it is truth spoken from their bodes. And body-truth, lived truth, body-experience is powerful because it is truth than cannot be refuted. And when we read the work by a writer writing body-truth, we feel it in our bodies as well. Anzaldúa wrote about the borderlands and culture and language and spirituality—but she spoke from the lived experience of her body, and even now, thirty years after it was published, the book still speaks powerfully to people from very diverse backgrounds.

In addition to everything else they are, I believe writing and reading are also physical and energetic exchanges. Language infused with energy transfers that energy from writer to reader. In the same way, language from the body transfers from one body to another.

The most popular poem by far in my first book (furia) was “I come from women illiterate and rough-skinned.” I think it captured people’s attention because it directly spoke to being the daughter of my mother’s lived body experience, to being the daughter of all my mothers’ lived truths. In that poem I'd also wanted to say something about the lives of poor bodies of color—how they’re stereotypically seen as bodies living a life that is solely a physical experience and not also a spiritual, intellectual, emotional, and artistic experience.

With flesh to bone, my short story collection, the entire focus of the book was violence and healing and so again, I returned to body-truths, to body as witness, body as history and future, body as language and art and prayer, body as the site of transformation.

Blood Sugar Canto took everything I had. I wrote the last poems for it in 2014 and it shorted out my circuits for a few years. But I wanted it to be as true as I could make it.

For the book projects I’m working on now, the greatest challenge has been learning all over again—with these new themes and characters and ideas—how to remain as close as possible to the truth of the body.

SUSTO

the old women say it is the accumulated weight

of so many sustos that cause diabetes

susto: not fright but trauma

and stress and shock and loss and grief

which susto do i blame for all this

which susto was the first to begin breaking down my resistance which susto was

the last straw

the knife that gutted me that drove me to the edge

pushed my body over which susto claimed victory and drove my very cells to

refuse the gifts of my blood

how do i name them all and once

named how do i uproot them unmake them and how do i heal

what’s left behind

This book is so brave. It weaves together health and heritage, the importance of family and the ways family can save you; it can also be read as a series of songs that speak back to doctors who colonize and ignore brown bodies. I’m amazed that you did so much in one book! What compelled you to write Blood Sugar Canto?

At the end of 2010, my first collection of poetry had just been published. I knew I wanted to try writing a whole collection of poems with some thematic core. I asked myself what was I struggling with the most in my life—what did I need most to figure out? The first thing that came to me was diabetes. By that point, I’d been an insulin-dependent diabetic for two and a half years. My youngest brother, who lived with me, had already given up driving for a year because his feet and legs had become so numb that he couldn’t gauge the pressure he was applying to the gas and brake pedal. My father, who’d been diabetic for at least twenty-four years of his life, had just passed away.

I had a lot of feelings and issues and traumas about diabetes that I needed to sort through. I’d gone to poetry for everything else—to work through discrimination, alienation, culture shock, love, heartbreak, grief...to find my voice, my sexuality, and my language.

At the time, I could only think of a handful of poems by Sherman Alexie on the subject of being diabetic, and so I thought, I’m going to write the book that I wish existed. So that I wouldn’t feel so alone in my diabetic body—so that I could explore this experience of being diabetic as a poet, poetry being the only way I’d ever been able to make sense of anything.

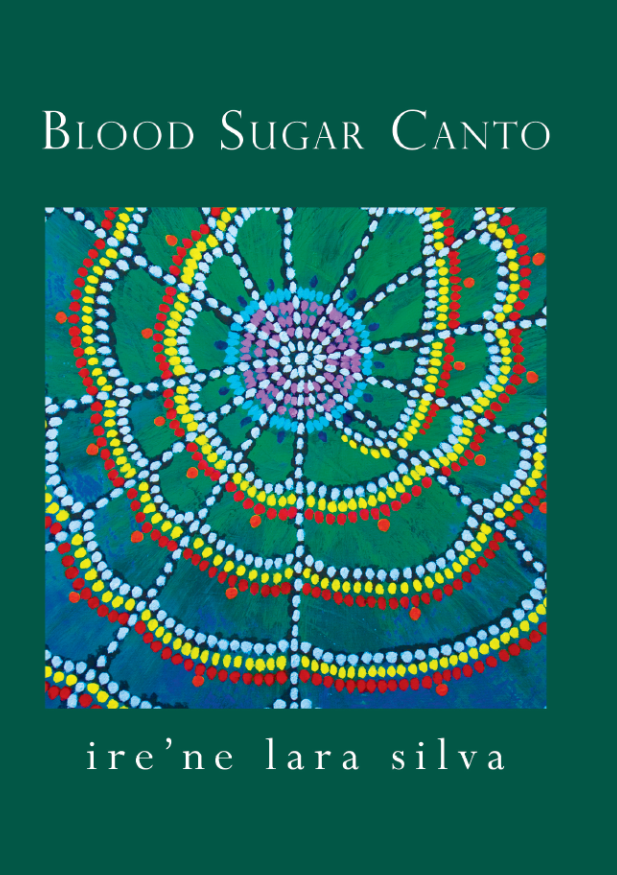

I started making a list. I knew I wanted to write a poem about amputation, my father’s greatest fear. I wanted to write a poem about tequila. One about South Texas. I wanted to figure out how to write a diabetic love song. I had to write about despair and depression. I wanted to write about my experiences with doctors. And from there, the list just grew and grew. I had many, many conversations with my brother about what else needed to be written about our experience—as people, as a part of our family, as a part of our communities. At least a third of the poems in BSC were prompts or ideas he suggested. The cover art is a painting by my brother that he was working on while I was revising the book.

The more I wrote the more clear it became that what I wanted to do was write a book that would inspire conversations. A book that would make people with diabetes or other chronic illnesses feel less alone. A book that might help non-diabetics glimpse what diabetes meant in a life. A book that would help family members or community members establish a dialogue. A book that might make doctors and other health professionals understand their patients a bit better or treat them more humanely. A book that would share my particular experience—a woman of color, Mexican-American, Indigenous, queer, from the border, born in poverty, an artist—living with diabetes.

Purchase Blood Sugar Canto

from Saddle Road Press.

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: The image shows the book cover. The cover is green with the book title and author's name in white. The title is in small caps while the author's name does not include capital letters. Between the title and author is a square picture that shows a spiderweb made of colored lights. The radial threads are white, while the viscid threads are depicted with a row of white lights, a row of yellow lights, and an outermost row of red lights. The very center of the web is white. It is surrounded by a three rings of lavender lights and one ring of light blue lights.

My favorite poem in this book is "the diabetic lover," because it allows, in the midst of fear, shame, and uncertainty, a way for desire and joy to exist. Please say more about that particular poem—the process of writing it, what it means to you, anything you like.

I was watching some show—I don’t even know what—and the couple was raiding the refrigerator for whip cream and chocolate syrup and who knows what else, and it occurred to me that something that people would take for granted as fun or as a little adventurous would be something that a diabetic person would have to consider seriously before including in their sex play. If you think about it, nobody talks about what the sugar content is in flavored lubes or edible underwear or anything else.

But returning to the moment of writing that poem, it made me giggle to think of all those nutritional guides I’ve seen that list foods recommended for people with diabetes being consulted before heading to bed with items from the fridge.

As I went deeper into the poem, it became more about reclaiming sexual desire, pleasure, and agency over one’s body. So much of the time, the chronically ill body is seen as just that—chronically ill to the exclusion of everything else. But we are more than our illness—we are still living and participating in everything that life offers. And while the 25 granules of brown sugar speak to the limitations and awareness that diabetes imposes and requires, they map out the lover’s body in small explosions of sweetness and sensation. By the end of the poem, I hope, the reader is focused entirely on pleasure and on the relationship between the lovers.

THE DIABETIC LOVER

it’s not recommended, my love

that i cover your body with whip crème

and chocolate syrup

maraschino cherries

for aesthetic emphasis

i could not dust you

with enough whey protein

to make up for all

those empty carbohydrates

i cannot tongue red wine

from your body

or drink shots

out of your navel

since that

would make me

quite literally

sick

but the thought of

grilled chicken breast

and veggies with half

a cup of brown rice

served on your skin

does not seem

conducive to

a night of passion

no for sweetness

all i’d need would be

twenty five granules of

turbinado raw cane sugar

oh so carefully counted

one on your left temple

that’s where i’d begin

dark sweetness

exploding against my tongue

dark sweetness

in the scent of your hair

three on your tongue

while i pulled on your

lower lip with my teeth

one along your jaw

one down your neck and

one on your clavicle

i see sunlight and lush

green leaves playing

over your skin

two on one shoulder

and three trailing down

diagonally to your hip

i meant to use only my

lips mouth tongue

but my hands can’t

resist following the

waves of your body

the ocean crashing

in my ears

i’d take five

in the palm of

my hand

and rasp them against

the tips of your

breasts

drink in your gasp

then hunt for every bit

of sugar cane dust

while you sighed

three down

your abdomen

like far-flung

constellations

my mouth

on your belly

always makes you

curl up

i’d catch one foot

and then the other

place a granule

on each arch

since raw cane sugar

doesn’t dissolve at

the first touch

i’d roll one granule

up your calf

another from your

knee to your thigh

one from your

thigh to your hip

and then i’d find

my twenty-five granules

gone

but no worries, my love

i’d murmur against

the apex of your thighs

your sweetness

always renders

any more

excessive

and

unnecessary

Please share with our readers a list of 5-10 books you think we should read right now.

Joe Jimenez: The Possibilities of Mud (Korima Press, 2014) and look out for his forthcoming collection which won the Letras Latinas/Red Hen prize and will be published in 2019.

Sarah A. Chavez: All Day, Talking (Dancing Girl, 2014) and look out for her forthcoming collection, Hands That Break & Scar (Sundress Publications, 2017)

Barbara Jane Reyes: Diwata (BOA Editions, Ltd., 2010) and look out for her forthcoming collection, Invocation to Daughters (City Lights, 2017)

Those are all poetry collections I’ve absolutely loved.

Also wanted to mention a few books that are at the top of my to read list:

House Built on Ashes by Jose Antonio Rodriguez (University of Oklahoma Press, 2016)

Spill by Alexis Pauline Gumbs (Duke University Press, 2016)

Whereas by Layli Long Soldier (Graywolf Press, 2017)

And whenever I talk about writing from the body, I always end up mentioning the work of Jeanette Winterson, especially her collection of essays, Art Objects: Essays on Ecstasy and Effrontery, and her novels, Written on the Body, Gut Symmetries, and Sexing the Cherry.

Some Rogue Agent fans are just beginning to explore what making art about the body would look like for them. What advice would you give to someone just starting down the path toward writing poetry that features the body?

Promise yourself to tell the truth. And the more naked and vulnerable you feel, the closer you are to the truth.

Listen to your body and learn its languages and rhythms and energies.

I was talking to my friend Natalia Sylvester the other day (author of Chasing the Sun) and we agreed that if the writing was coming easy, then we were doing it wrong. The more difficult, the more challenging the writing was, the more we knew we were on the right track.

Strengthen your resolve before you show your work to the world. Depending on who’s around you, it might meet with condescension, incomprehension, or opposition (or worse). Figure out who will support and challenge you to find your voice and your work.

And lastly, read work not because you “should,” but because it speaks to your body. Because it makes you start, because it makes you weep. Because you feel its electricity zooming around inside you. You never forget the work that lives in your body that way. For me it’s Juan Rulfo and Toni Morrison and Audre Lorde and Hafiz and e.e. cummings and Leslie Marmon Silko and many, many more.

ire’ne lara silva is the author of two poetry collections, furia (Mouthfeel Press, 2010) and Blood Sugar Canto (Saddle Road Press, 2016), an e-chapbook, Enduring Azucares, (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2015), as well as a short story collection, flesh to bone (Aunt Lute Books, 2013) which won the Premio Aztlán. She and poet Dan Vera are also the co-editors of Imaniman: Poets Writing in the Anzaldúan Borderlands, (Aunt Lute Books, 2017), a collection of poetry and essays. ire’ne is the recipient of the final Alfredo Cisneros del Moral Award, the Fiction Finalist for AROHO’s 2013 Gift of Freedom Award, and the 2008 recipient of the Gloria Anzaldúa Milagro Award. ire'ne was recently named a 2016-2018 Texas Touring Roster Artist. Visit her website at irenelarasilva.wordpress.com .

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: ire’ne lara silva stands against a backdrop of plants and yellow flowers. She wears a blue shirt with a darker blue design around the V-neckline. She has shoulder-length black curls, brown eyes, and brown penciled eyebrows.

Jacklyn Janeksela

BELLY BONES

from down there, she cries//from down where, it whispers//from down here, she cries

no one expected her voice, not even she or her or they

and she explains down there is like this::

beneath the ocean that splits open shells where mermaids

spool and thread sea moss to make wigs for mermen

just under the lid of a coffin, it closed her life off for good

without warning, it still shakes under new moons

buried in the foothills of a wide open plain covered

with rocks that mimic spiders that mimic tumbleweeds that mimic hair

an outer space in reverse where the stars vibrate a mighty song

and ripple time like a broken mirror, it’s all soundless

below her pillow where she trembles from between death and orgasm, the

hand that holds her there is her own but it’s also theirs

and it could be yours, too

Jessica Abughattas

MAMA

after Sylvia Plath

First they tell her how beautiful she is, then they turn their gaze toward you,

She looks like her father, your daughter doesn’t look like you

The same beauty mark and his last name from Peru

Father’s mother hated mama and you have her eyes steel blue

You tiptoe around mama and mama tiptoes around you

If today is good mama might bake a cake and let you stir the goo

and if you are good and quiet, she might let you lick the spoon

On bad days mama stays in bed and shuts herself in her room

You sit in front of the bannister and stick your fat legs through

You are solitude and rue, mama says, an animal from the zoo

You hate your feet, the sounds they make, when mama calls for you

to bring the pills, bring the bottles, boil the water for winter stew

Your steps inconvenience mama, mama is inconvenience too

Mama is the wicked witch on mute, air in place of the cackling shrew

When mama emerges from her lair with smile and sinew

She brushes your hair, irons your clothes and calls you honey dew

Then mama snaps back to black before the bottle can unscrew

It’s back back back to the bannister and dreams you might fall through

Dreams of screams that might make mama, mama finally finally listen to you

You heard mama say she never wanted children

What mama wants is a silk-white shirt, the funeral dirge, a house devoid of you

When you’re twenty she’s hip-less and gaunt, thinks she looks better than you

What rattles in mama’s brain so hard rattles in yours too

Why did you do this to mama, why did mama do this to you

Mama, mama you bitch, your 6 year old was stronger than you

Mama is the big house forever, vacant as has always been true

Five welts across your face, one for each finger not meant for you

You do not do, you do not do

That’s my daughter, mama says, thin and blonde and blue

She looks like her father but she’s a good little reader, and she didn’t get that from you

and mama says she is so, she is so, she is so, so proud of you

Mama is a dress made of lips and breasts drooping down like Pablo’s period in blue

Mama is Spain tearing flesh from flesh, leaves the wounds unstitched in you

You are Guernica, the hand that holds the lightbulb, then kaboom,

Mama needs her pills for the ache in her head, the ache in her back, the ache the ache of you,

Mama aches through the house, and the house, the house aches when she drips through

She says she’s like Dali, as she stains the walls in every starving hue, and the walls,

the walls ache too.

Leah Welborn

CAGE MATCH

I wager most every woman or girl

has had to lie down sometime when she didn’t want to

and it was

just my time. He said “you got pretty titties little baby”

and he winked, licked his withered old man lips.

I had just turned eight and a tiny

baseball bat beat against the inside

of my cage, a steady tattoo of fear and self-loathing.

Decades later my ribs are chattering like children.

They ask:

are we playing fetch, or dead?

And later when they ask about the blur

(as if my flesh could bring me back together), I tell them simply

It was magical. It was a small round bruise on our sins.

I run my fingernails across the smooth bones, pack them away

in folds of fat for safe-keeping

alongside their bejeweled sternum, natty as an ascot,

and tie the whole package

with pink silk ribbon.

Cheyenne Nimes

THE LOVERS.

If a meteorite is both large and moves fast enough, it glows at a degree often brighter than the sun. It blocks out the sun, the light the world appears in, the bruised light. Face-off. The Lovers is not an easy card in any deck. Their hot breath hits us in the face. Primal ember, prehensile tail, you wouldn’t believe something that big could come in that close & be so quiet. The enemy always tries to surprise you, to catch you off guard. The menace of an empty sky. You just keep upping the ante. To capture this on film you must be quick. Get on an even angle with your subject & shoot it straight on. Whatever town you’re in, just say that name. If you’re on the surface, float motionless. Don’t touch ground. The four card, the devil’s bedposts. Five is fever. Seven fishhook. You’re supposed to play out the hand you’re dealt. But you can’t conquer it, settle it, even own it. White reflects all visible frequencies, it sends back everything. Don’t look at me. Stepping toward earth and away again. A heart-shaped region. A single stone was observed to fall. The thing which was seen was not made out of the things that appear. She was wearing a cloak & a hood & a really burnt face. What it was in the end when the sun lifted itself off it. There’s no place left to run. Swinging in circles, under the influence of the gravity of another body. And the final escapist minutes. Revealing a layer of white gristle & dark muscle. Most knew what they were seeing before it hit the ground. But if they ever find her she won’t be herself.

Stephen Langlois

DEED OF ELECTROCHEMICAL TRANSFER

Artist statement:

I’m fascinated by the seeming mundanity of everyday forms and documents–and the ability to subvert their intended purpose by changing their language while retaining the general ordinariness of their framework. It’s a tactic we often see employed by parody and satire, though in conceiving DEED OF ELECTROCHEMICAL TRANSFER I wanted to see if/how I could take this one step further. Biochemistry is another area of fascination for me–particularly as someone being treated for clinical depression–and it seemed an interesting experiment to take an utterly banal-looking document and within it trace the minute, almost otherworldly inner workings of the nervous system. That those brief electrochemical signals passing between our synapses seem to be responsible for so much of what we think and feel as humans is both discomforting and absurd to me. With DEED OF ELECTROCHEMICAL TRANSFER I hope to highlight this discomfort and absurdity–and heighten it even further by creating what can never actually be: A document explaining–often over-explaining–that which is so often truly inexplicable.

Leslie Contreras Schwartz

AUDRE LORDE QUESTIONS ME, OR HOW TO BE A NOBODY, A LOSER, A ZERO

I'm nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody, too? — Emily Dickinson

I do not have the words

To say I exist

If I don’t, to some,

Not in the way that matters

Which matters in the same way that

Some girl finds herself

Sitting nude in school parking lot

An alley behind a factory or a darkened

Street by a bayou and forgot how

She forgot she was cold and naked

Forgot she was 15 but remembered

The years 4 and 5 and 6

Its brilliant streetlight of years

When he brings back her

Clothes and turns

On the days my leg, legs, feet, drag

Behind me. These are not the only days

My body feels the weight

Of Brock Turners behind a dumpster.

I am nobody

If not the black men

Whispering I can’t breathe

If I’ve heard and wake up the next day

Like I didn’t

Like the bent-over brown bodies in

The country’s long armed fields

As they inhale pesticides

That smells of loneliness and

Murder and if they keep smelling it

They believe it’s the scent of their mother’s warm bosom

That country of warmth

O, to climb into that—

The inside of a hotel room

Or a massage parlor or a cantina

Or a unairconditioned kitchen

Or a back room in that house

Or their parents’ room or a sister or

Brother’s room

Where money changes hands over

Their body

I am not them

But some other nobody

And when I bore this nobody in

This body it didn’t promise to disappear

Later—How do I say?

I don’t have the words

To even whisper or write or think

What it’s like to be someone’s bodily and

Still-living Abortion

America’s fetus

The one they’d rather not bury

Since the soil costs money to shovel

Always the cost of labor

And the ones that did

The hangings, they left the bodies

Under trees’ boughs swinging

Now they hang us

Within ourselves,

So only we can see

Where I, in turn,

Hear them like leaden bells

In my chest, the thud of

Limb against limb

This music is mine

And I have turned it

Into a drum

What tyrannies meant to force,

Choke, smother,

Sear my body

I will finish myself, taste

Its sharp purple pain,

Its throb of a pistol

Whip. As long as I feel

What you do to me,

I know I am still

Alive.

And the others?

This is where

We differ. Those

Are my bodies too

Because once I

Was the girl sitting in the alley

So if it is possible then why not

Me when I see them,

Sisters, brothers,

Myselfs, a bunch of nobodies

Who forgot how they got

Left on America’s side road.

All these no bodied nobodies.

I wave to you from the bottom

Of my chest

Where our nobodies all hang

And thump their inglorious

God-given body song.

Shevaun Brannigan

A JELLYFISH IN NIGHT WATERS

Unzip my dress to sand falling,

a heap on the floor where

I was. A shell, a shell, a row

of stingray’s teeth, shark’s tooth,

broken comb, porcelain shards,

a doll’s mouth,

jellyfish tentacle reaching

like an electric fence

around the whole goddamn thing.

The ocean mouths

my waist.

Water hurled itself against

the cliffs like a man against

a barricaded door.

Out in the bay,

the clouds darkened, the sky thickened,

my parents squabbled like seagulls.

Fish began to upturn around us, then the drizzle,

we started back.

The jellyfish

stings tight around my spine.

If I learned patience,

it was when my father taught me

to look for sharks’ teeth.

Sometimes sifting through the sand,

my hand filled with small translucent crabs

I rinsed away to keep searching.

Kim Sousa

DYSMORPHIA

2016

My body a foreign house, yours home.

Richard Howard, “The Difference”

I press cold hands under your shirt.

You push me away, pull me closer.

I say, poor circulation. My heart doesn’t like to do its job.

You offer me a perc, put the pill in my palm.

Its round shell is each skipped beat in this body.

I shake my head. Tap my nose,

the deviated septum there like an interjection.

Forever rift. Canyon of cartilage and bone.

Here, in my cigarette smoke bedroom, you

still don’t believe I’m in recovery.

I press the pill to your lips and watch you swallow

without consequence.

I kiss your mother’s lips tattooed on your neck,

the diamonds like sober stars in your ears.

I think I could stand here a long time—

breathing through this body’s confused chambers,

blue as the day I was born.

Issue 26 Contributors

Jessica Abughattas is a Palestinian American writer from Los Angeles. She is an MFA candidate at Antioch University, where she is the Poetry Editor of Lunch Ticket. Before pursuing an MFA in poetry, she interned at Write Bloody Publishing and served as Editor of CurrentsMagazine. Her poems appear (or are forthcoming) in Drunk in a Midnight Choir, Roanoke Review and elsewhere.

Shevaun Brannigan is a graduate of the Bennington Writing Seminars, as well as The Jiménez-Porter Writers' House at The University of Maryland. Her poems have appeared in such journals as Best New Poets, Rhino, Redivider, and Crab Orchard Review. She is a 2015 recipient of a Barbara Deming Memorial Fund grant. Her work can be found at shevaunbrannigan.com.

Jacklyn Janeksela is a wolf and a raven, a cluster of stars, & a direct descent of the divine feminine. she can be found at Thought Catalog, Luna Luna, The Feminist Wire, Split Lip; & elsewhere. she is in a post-punk band called the velblouds. her baby @ femalefilet. her chapbook fitting a witch//hexing the stitch forthcoming (The Operating System, 2017). she is an energy. find her @ hermetic hare for herbal astrology readings.

Stephen Langlois' work has appeared in Glimmer Train, The Portland Review, Lit Hub, Maudlin House, 3AM Magazine, Monkeybicycle, Matchbook, Necessary Fiction, and Heavy Feather Review, among others. He is a recipient of a The Center for Fiction’s NYC Emerging Writers Fellowship as well as a writing residency from the Blue Mountain Center. He also hosts BREW: An Evening of Literary Works and serves as the fiction editor for FLAPPERHOUSE. Visit him at www.stephenmlanglois.com.

Amy Miller Amy Miller’s poetry has appeared in Nimrod, Tinderbox, Willow Springs, ZYZZYVA, and other journals. Her chapbooks include I Am on a River and Cannot Answer (BOAAT Press) and Rough House (White Knuckle Press), and she won the Cultural Center of Cape Cod National Poetry Competition, judged by Tony Hoagland, and has been a finalist for the Pablo Neruda Prize and 49th Parallel Award. She lives in Ashland, Oregon, and blogs at writers-island.blogspot.com.

Cheyenne Nimes is a cross-genre writer living by the Great Salt Lake. Recipient of an NEA in poetry, she attended San Francisco State University and Iowa.

Leslie Contreras Schwartz is a writer concerned with the experiences of women and girls, and turning stories of victimhood into stories of survival. She is currently working on a novel about human trafficking based in Houston, her hometown and where she continues to live with her family. Her first book, Fuego, was published in March 2016 by St. Julian Press. She earned an MFA in poetry Warren Wilson College. Her work has appeared or is upcoming in The Collagist, Tinderbox Literary Journal, Texas Review and other publications.

Ana C. H. Silva lives in NYC and Olive, NY. Her poetry has been published in Podium, Mom Egg Review, the nth position, Snow Monkey, Anemone Sidecar, Chronogram, and Stepaway Magazine. She won the inaugural Rachel Wetzsteon Memorial Poetry Prize at the 92nd St. Y Unterberg PoetryCenter. Ana recently created a community-based collaborative poetry project called "Olive Couplets."

ire'ne lara silva ire’ne lara silva is the author of two poetry collections, furia (Mouthfeel Press, 2010) and Blood Sugar Canto (Saddle Road Press, 2016), an e-chapbook, Enduring Azucares, (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2015), as well as a short story collection, flesh to bone (Aunt Lute Books, 2013) which won the Premio Aztlán. She and poet Dan Vera are also the co-editors of Imaniman: Poets Writing in the Anzaldúan Borderlands, (Aunt Lute Books, 2017), a collection of poetry and essays. ire’ne is the recipient of the final Alfredo Cisneros del Moral Award, the Fiction Finalist for AROHO’s 2013 Gift of Freedom Award, and the 2008 recipient of the Gloria Anzaldúa Milagro Award. ire'ne was recently named a 2016-2018 Texas Touring Roster Artist. Visit her website at irenelarasilva.wordpress.com

Kim Sousa was born in Goiânia, Goiás (Brazil) and raised in Austin, Texas. She currently lives in Pittsburgh with two illiterate pugs. Her work was most recently published, or is forthcoming, in Poet Lore, PEN & The Rattling Wall’s post-election anthology, Only Light Can DoThat, and The Pittsburgh Poetry Review. You can find her at kdowsousa.wordpress.com.

Jessica L. Walsh is author of How to Break My Neck (ELJ, 2015) as well as two chapbooks. Her second collection, Banished, will be published in 2017 by Red Paint Hill. Most recently her work has appeared in Yellow Chair Review, Whale Road Review, Tinderbox, Midwestern Gothic, and more. She has been nominated for Best New Poets, Bettering the Net, and the Pushcart Prize.

Leah Welborn is a feminist poet/writer who lives in Denver, Colorado with her two cats. By day, she's a copywriter for a major cannabis company. She earned an MFA from Antioch University and her work has appeared in Contrary, Connotation Press, Poets and Artists, Mental Floss, and various other print and online journals and magazines. She tweets @welbornleah.